Scientists have successfully hatched Irukandji eggs. Here’s why that’s important

A breakthrough by Australian marine scientists means they’ll be able to at last unlock the secrets of one of the world’s most dangerous creatures.By Sheree Marris • December 23, 2021 • Reading Time: 8 Minutes • Print this page Research assistant and aquarist Sally Turner monitors the behaviour of captive-bred Irukandji jellyfish. Image credit: Sheree Marris

Research assistant and aquarist Sally Turner monitors the behaviour of captive-bred Irukandji jellyfish. Image credit: Sheree Marris

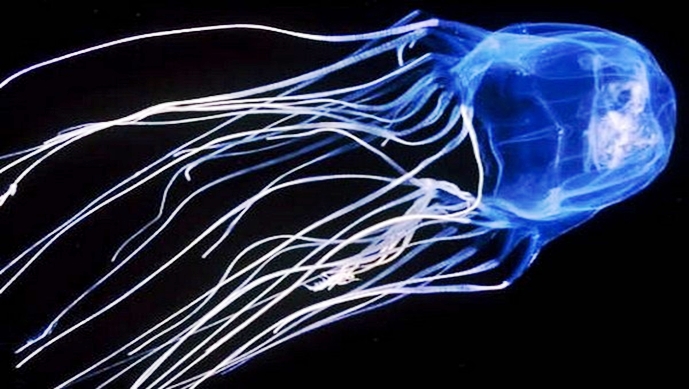

The Irukandji jellyfish could have sprung from the fertile imagination of a sci-fi horror writer. It looks deceptively insignificant and benign, but its entire body is a biological booby trap. In most jellyfish it’s only the tentacles that are studded with the minuscule harpoon-like, venom-loaded stinging cells known as nematocysts. But in Irukandji the bell is also armed with these toxic weapons – as many as 5000 per square centimetre. An encounter with an Irukandji can have an adult human soon fighting for their life. Like most jellyfish, the Irukandji is transparent, but it’s tiny – no more than 2.5cm wide – so you’re unlikely to see it coming and stay out of its way. And even if you did, those tentacles are extendable, reaching out to four times their relaxed length.

This jellyfish was named after the Irukandji people, traditional fishers whose Country includes the sea off the coastal regions near Cairns, Queensland. Although this was the area where the jellyfish was first recognised, its distribution is much wider. And with more people venturing into the waters where they occur, reports of stings are becoming increasingly common and scientific scrutiny of the Irukandji has been mounting.

But research on the species in the wild has had limitations. Although it’s been possible to collect these tiny, near-invisible creatures in their natural habitat at night using lights, scientists have been struggling to study them in a controlled laboratory environment and haven’t been able to breed them in captivity.

Now in a world-first, Professor Jamie Seymour and his team of jellyfish researchers working in a lab dubbed the eduQuarium at James Cook University’s Cairns campus have managed to breed the Irukandji in captivity. It’s an achievement that’s been 20 years in the making and is a vital step forward in the mitigation of the threat posed by this intriguing jellyfish species.

It also means that we finally have a chance to learn the secrets of a creature that produces one of the most diabolically painful experiences known to humans.

Irukandji–human encounters

Jamie Seymour is a global expert on jellyfish, as well as many other dangerous sea creatures. Protected in tanks stretching around the walls of his lab is a range of deadly marine animals, from colourful crustaceans that literally punch their prey into submission, to slimy snails with weapons stuffed up their noses and sand assassins with blade-like claws that would make Freddy Krueger cower.

But it’s the Irukandji jellyfish that are the stars of this show in their futuristic round tanks, designed without corners to prevent damaging the soft bodies of these hard-core carnivores.

Jamie understands the pain of an Irukandji sting better than most. It’s one of the risks of his research and he’s been stung 11 times so far. “Yep, I’ve experienced the pain of an Irukandji sting many times in the past. It’s not something I’m proud of and it’s 11 mistakes I wish I hadn’t made,” he admits. “So on a more positive note, at least I’m intimately familiar with the incredible pain and discomfort that victims can suffer, and I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy.”

As with many things about this poorly understood jellyfish, its lethal weaponry of explosive and spring-loaded venomous harpoons is unique in the animal kingdom. Certainly people have died following envenomation by Irukandji, with victims succumbing to the effects of potent toxins and incredible pain, but it’s rare. There are only two recorded deaths.

But there’s concern that these jellyfish may have been responsible for more deaths than those attributed directly to them and that for various reasons, including the impact of climate change on their distribution, Irukandji–human encounters are on the rise. And that’s what makes the discovery of how to breed them so important.

Read the rest of the article here