Jo Nova writes:

Plastics are not forever: Bugs already evolved 30,000 new plastic eating enzymes

Plastics are a free dinner for life on Earth so it was just a matter of time before microbes evolved to eat it.

A PET bottle normally takes 16 – 48 years to break down, but if it were lunch for microflora it would take weeks instead. Hydrocarbons are ultimately just different forms of C-H-O waiting to be liberated as carbon dioxide and water. The only question was “how long” it would take bacteria and fungi to break those unusual bonds.

Sooner or later all plastic will be biodegradable.

Polyethylene-terephthalate (PET)

The first bacteria known to chew through PET bottles was discovered at a Japanese rubbish dump in 2016. But we had no idea then just how advanced the microbial world of plastic processing was.

A new study shows. Instead of hunting for single bacteria Zrimec et al mined through collected metagenomes of soil and ocean and found not just 5 or 10 new enzymes but 30,000. It appears that they could metabolize at least ten different types of plastic.

And in places where there was more plastic pollution, there were more enzymes. All over the world a whole new ecosystem is rising out of the puddles and bubbles and grains of sand.

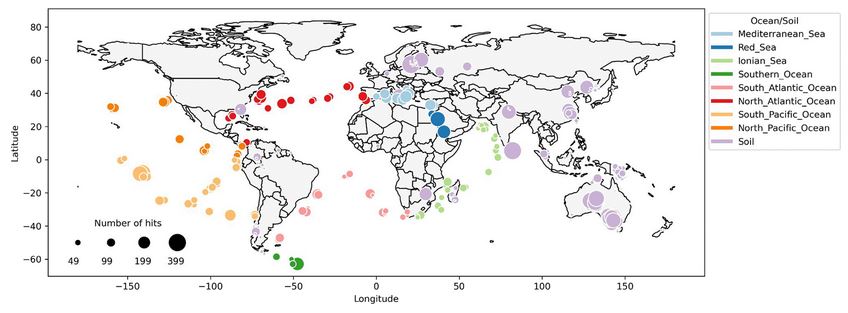

Enzymes that degrade plastics are found all over the world

FIG 2 Plastic-degrading enzymes across the global microbiome. Depicted are 11,906 enzyme hits in the ocean and 18,119 in the soil data sets, obtained by constructing HMMs of known plastic-degrading enzymes and querying them across metagenomic sequencing data sets. The potential to degrade up to 10 and 9 different plastic types was observed in the respective ocean and soil fractions (Fig. S3A).

Mother Nature has a big toolshed of genes to play with:

With a library like this, is it any wonder life on Earth could find and amplify the right tools to process plastics?

For example, global ocean sampling revealed over 40 million mostly novel nonredundant genes from 35,000 species (35), whereas over 99% of the ∼160 million genes identified in global topsoil cannot be found in any previous microbial gene catalogue (34)

So there are 200 million genes to work with.

Bugs across globe are evolving to eat plastic, study finds

Damian Carrington, The Guardian, 15 Dec 2021

The explosion of plastic production in the past 70 years, from 2m tonnes to 380m tonnes a year, had given microbes time to evolve to deal with plastic, the researchers said. The study, published in the journal Microbial Ecology, started by compiling a dataset of 95 microbial enzymes already known to degrade plastic, often found in bacteria in rubbish dumps and similar places rife with plastic.

About 12,000 of the new enzymes were found in ocean samples, taken at 67 locations and at three different depths. The results showed consistently higher levels of degrading enzymes at deeper levels, matching the higher levels of plastic pollution known to exist at lower depths.

The soil samples were taken from 169 locations in 38 countries and 11 different habitats and contained 18,000 plastic-degrading enzymes. Soils are known to contain more plastics with phthalate additives than the oceans and the researchers found more enzymes that attack these chemicals in the land samples.

Nearly 60% of the new enzymes did not fit into any known enzyme classes, the scientists said, suggesting these molecules degrade plastics in ways that were previously unknown.

The not so apocalyptic plastic crisis

The new 250 page “Consensus” Study (their words) by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, is as out of date and useless as it sounds. While it is scoring headlines, scaring us about accumulating plastics, it largely writes off the idea that microbes will evolve to degrade plastic, saying “measurable biodegradation (complete carbon utilization by microbes) in the environment has not been observed.” Which is one of those true but useless statements.

Some 40 year old theory says it won’t happen:

Plastics with hydrolysable chemical backbones (e.g., PET and polyurethanes) may be more susceptible to enzymatic degradation and eventual biodegradation than those with carbon-carbon backbones (Amaral- Zettler, Zettler, and Mincer 2020), as illustrated by the discovery of PET-degrading bacteria isolated from a bottle recycling plant (Yoshida et al. 2016). However, Oberbeckmann and Labrenz (2020) argue, based upon Alexander’s (1975) paradigm on microbial metabolism of a substrate, that the very low bioavailability and relatively low concentration of plastics in the ocean together with their chemical stability render these molecules very unlikely candidates for biodegradation by marine microbes, despite their potential as an energy and carbon source.

But if plastics are so tiny and low in concentration, it’s a big “so what” — they are unlikely to be a problem. If they were concentrated in one place or collected in an organism, they could be bad, but then, of course, they also become fodder for microbes.

The bottom line: We don’t want to drown dolphins and trap turtles, but we shouldn’t demonize plastics either.

Don’t throw rubbish in the ocean or toss hype in national news. It’s all litter.

Hat tip to Kip Hansen at Watts Up.

REFERENCES

Zrimec et al (2021) Plastic-Degrading Potential across the Global Microbiome Correlates with Recent Pollution Trends, ASM Journals mBio Vol. 12, No. 5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02155-21

Reckoning with the U.S. Role in Global Ocean Plastic Waste, (2021) ISBN 978-0-309-45885-6 | DOI 10.17226/26132 https://www.nap.edu/download/26132